THOUGH T.S. ELIOT FAMOUSLY wrote in The Wasteland that “April is the cruellest month,” when April finally rolls around here in the Northwest with its changeable weather and long-awaited flowers, I’m usually looking for a slightly more hopeful take on it. I’ve written before about my joy in seasonal reading and, this time of year I turn to Elizabeth von Arnim’s classic 1922 novel, The Enchanted April. (A quick note: the beautifully filmed 1991 movie dropped the “The” in the title, which I actually prefer, so I’ll be referring to it that way throughout.)

Writers hear so much advice about getting into your narrative quickly, making sure you have a strong “hook” or inciting incident, and keeping your characters moving, etc., etc.

I have to admit that part of my subversive delight in the book is that it appears to disregard all that well-meaning (and tedious) advice. It’s essentially a book about four women going away to think, to reflect on their lives—what’s working and what isn’t—and to consider whether change is possible. Somehow its leisurely pacing gives the reader time to enter the interior life of each woman and really experience their inner journeys. And it works, as the fact that the novel is celebrating the one-hundred-year anniversary of its publication this year attests.

On a dark February afternoon, Lottie Wilkins and Rose Arbuthnot see this captivating advertisement in the Agony Column of The Times:

To those who appreciate wistaria and sunshine. Small mediaeval Italian castle on the shores of the Mediterranean to be let furnished for the month of April.

“Why don’t we try and get it?” Lottie asks Rose as the rain pours down outside their London windows. “Why it would really be being unselfish to go away and be happy for a little, because we would come back so much nicer. . . . and you look exactly as if you wanted it as much as I do—as if you ought to . . . have something happy happen to you.”

Though the two women are still in their 20s, they’re already years into unsatisfying marriages. Lottie’s husband, Mellersh, is a well-meaning but overbearing solicitor who “encouraged thrift, except that branch of it which got into his food. He did not call that thrift, he called it bad housekeeping.” Rose’s once-beloved husband, Frederick, “had been the kind of husband whose wife betakes herself early to the feet of God.” Since Rose is very religious and Frederick makes his living by writing salacious books (under a pseudonym) about the mistresses of kings, she channels her embarrassment and regret into charitable works, which may do good but leave her soul empty.

Lottie and Rose quickly discover they cannot afford San Salvatore on their own, so they advertise for companions and receive only two responses. Lady Caroline Dester, a beautiful 28-year-old socialite who is beginning to suspect that her life is “a great noise about nothing,” and feels “one great longing . . . to get away from everybody she had ever known,” and Mrs. Fisher, an elderly widow, mourning the greatness of the eminent Victorians she once knew, who only wants “to be allowed to sit quiet in the sun and remember.”

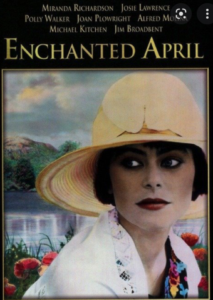

“I suppose you realize, don’t you, that we’ve got to heaven?” Lottie (who’s played by Josie Lawrence in the movie) says to Rose (Miranda Richardson) and Mrs. Fisher (Joan Plowright) on their first morning at San Salvatore. Quickly concluding that she can’t be happy in heaven without Mellersh (even though she’s just spent a month trying to get away from him), Lottie immediately writes and asks him to join her. Rose wishes she could write and ask Frederick to join her too but she’s afraid he would decline, which would hurt her tender heart even further. Mrs. Fisher is struck by a strange restlessness and a longing to burst free of her old life, but is too embarrassed “at her age” to share it with the younger women. And Lady Caroline (known to her family as Scrap) ponders her possible sets of 28 years and concludes—it’s an especially memorable scene in the movie, as a young, ravishingly beautiful Polly Walker, sitting in a vintage deck chair in the garden holding a parasol over her head, thinks, “I’ve wasted so much time being beautiful.”

So, there’s the setting, and the rest is pure fun. Von Arnim is an amusing and witty writer: “Have you noticed,” Lottie asks the first night at dinner, “how difficult it is to be improper without men?” The men do eventually arrive, but though all three of them (the third is Mr. Briggs, the owner of the castle) come for selfish reasons of their own, San Salvatore works its magic on them, and right relationships and happiness are eventually restored.

Elizabeth von Arnim was born in Australia in 1866. Raised in England, she married the German Count von Arnim, whom she referred to as “the Man of Wrath” in her first book Elizabeth and Her German Garden. When the Count went into debt and was sent to prison for fraud, the Countess adopted the pen name “Elizabeth” and began writing books to make money. He died in 1910, and Elizabeth went on to a series of affairs and a disastrous marriage to Francis, the second Earl Russell. Enchanted April was written after she’d visited Castello Brown near Portofino, which became San Salvatore.

She was desperate for money by that point, and wrote the novel quite quickly. I like to think that if she’d had more time she would have come up with the ending to Lady Caroline’s story that it deserves, which fortunately the movie does splendidly.

So, give yourself a treat and, for an hour and thirty-five minutes, experience your own Enchanted April in Italy. I wish I could give you a whole month, but I promise this is the next best thing!

Featured image: Samuele Errico Piccarini, courtesy unsplash.com

Movie image: courtesy Rotten Tomatoes

Thank you, Robin! I love book recommendations and seems to “collect” them on Post-it’s and lovely note papers. You’ve inspired me once again to return to my happy place, the library. 💞

You have a treat in store, Donna! So happy you’re inspired to read The Enchanted April. Be sure and watch the movie too!